[ad_1]

On a thru hike, you experience a different reality. Returning is a breakup with that reality.

I wouldn’t be the first person to say that ending a thru hike feels like a breakup.

Cue Elina Osborne’s opening line to her iconic Pacific Crest Trail love letter: “They say your first thru hike is like your first love.”

To paraphrase what my PCT friend and fellow Trek blogger, Refill, wrote in his terminus post: a thru hike is something beautiful and painful that you eventually have to leave in order to fully appreciate and heal from, but that leaving was always going to hurt. Leaving hurt because you loved it.

It was only once I had experienced it myself that I began to grasp this.

Hiking through a rainstorm and eating conciliatory chocolate.

The disorienting thing about the feeling of returning to “reality” from a long trail is that the “trail”—here insert whatever long trail of your choice—feels like it is reality. Or even that it is more than reality.

By that I mean the process of thru hiking, its churning of your body and mind through its wash cycle of weather and other mishaps day after day after day after interminable and frustrating and aggravating day…it eventually loosens you from what you were before. Perhaps you are less clean, but you are more pure. You are raw.

In my own words, this is what I felt in the immediate days after finishing the Pacific Crest Trail in 2023, a banner year for the California snowpack, in response to a friend’s question on what was different about me post-trail:

“The biggest thing is that I’m much more comfortable with unknowns. I have a lot more confidence in myself. I have nothing to prove to anyone, or to myself. I have a deep belief that I can do ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ is, because I have already done this insane thing in a year where people said it was ‘impossible’ or ‘reckless’. I have a deep belief that people are good, that people will help me, that I can impact others, that everyone has a story worth listening to, that things will work out. I have a mindset of abundance, not scarcity. My priorities have been clarified as a result of being tumbled and strained through the stress and the monastic lifestyle of the trail. There is a loosening, like my spirit was so wound up before and now I’ve been able to exhale. Like everything has been emptied and now I am open.”

It is a pared-down, pure existence, as so many have preached before me. You are reduced to your own power, and that in itself is empowering. Finishing a thru hike is a departure from this reality you’ve lived for months on end. Leaving that powerful experience behind is heartbreaking.

Returning to ‘real life’ after the trail feels like ending a spiritual connection with Nature only to replace it with a cheapened reality. We can’t each follow Thoreau’s lead and create our own Waldens to evade the tax on our spirits. You can’t stay on trail forever.

In our breakup with the trail, we compare our modern world and its comforts and cages against the freedom and wildness of nature. Once you’ve tasted this Eden, normal ‘reality’ seems bland.

Reality on trail feels more alive to you because you were there, fully. Present, attentive, awake, aware. Open. Like the purest form of love, you were vulnerable to all of it, whether you liked it or not, whether you asked for it or not, all of it in reality: the good, the bad, the wonder, the loss, the pain, the tension, the actual real wild joy—the heartbeat of the moment. And that is what has allowed it to sink so deeply into your marrow. This is what has made the breakup so hard.

It is a narrow strip of earth, extending very very far, that provides the basis for a journey of the spirit. It is like you: not at the end as it was at the beginning, and yet it is. You start as one person at the southern terminus, surrounded by desert, and end as a different person in the lush forests of the northern terminus – and yet you are the same person, and these are two bookends of the same line on a map.

A section of the Pacific Crest Trail in Washington.

Little moments in your new reality make you miss the trail

This is how it feels to break up with the trail:

Three days after finishing at the northern terminus together, you’re on your way to the airport to drop off your two French hiking partners, with whom you shared more than half the major markers of the trail. You take them to Seattle’s flagship REI.

You will buckle, literally, when you casually flip through Joshua Powell’s PCT book at this REI, because in the book’s visual compendium you will find a hand-drawn sketch of that one porch at that one general store in Sierra City where you consumed the first one pound burger of your life, after which you gave yourself a paper towel shower in the public restroom and continued hiking.

You will see a page full of hand-drawn Snickers bars that brings to mind specific faces and you will laugh and laugh and laugh. When you inevitably are missing them, you will come back to the thirty seconds of opening video that you feel capture these personalities.

Members of the author’s PCT Sierra team members and friends.

As you page through, you will accidentally catch the briefest glance at a collection of jagged map lines in the corner and realize instantly that it’s that bit of Section K near Mica Lake. You remember it as the day with the innumerable switchbacks on which you later screamed into the dark unfeeling valley, and meanwhile kept staring at your map as if memorizing it would help you get up the mountain any faster.

It will be revelatory: the idea that anyone else who has hiked this trail will recognize themselves in any part of the trail – they will have their own memories of their own anguish or celebration at any point along this 2,650 mile line.

Grief, in any form, for any thing, feels heavy. Post-trail depression is a kind of grief. The English word ‘grief’ is derived from the Latin word gravare: to make heavy; which is itself derived from the Latin gravis: weighty. It was something important, something that carried weight, something that can suddenly make you heavy. That is why it hits you like that, in REI. Grieving for the loss of your former reality. And you are only three days off-trail, at that point.

Like this, ordinary moments in your new reality will trigger floods of trail memories.

You will cry when your gift of a fellow 2023 hiker’s unbelievable photobook, which captures all the same scenes and seasons you saw and cursed and wondered and wandered, is delivered to your mother. Like many mothers of the PCT, she was the one who put your resupply boxes in the mail, and added the extra stash of dried mango you did not ask for. She was the one driving all over Washington – your home state – to meet you and your French friends while bringing them brie and baguettes and sorry mom we added a German friend too, can he squeeze in the car? She is forever trying to translate you whose young adulthood is so different from hers; she was the one trying to figure out exactly what you mean when you ask her to buy you a Knorr rice side and a Lenny & Larry’s cookie, white chocolate only.

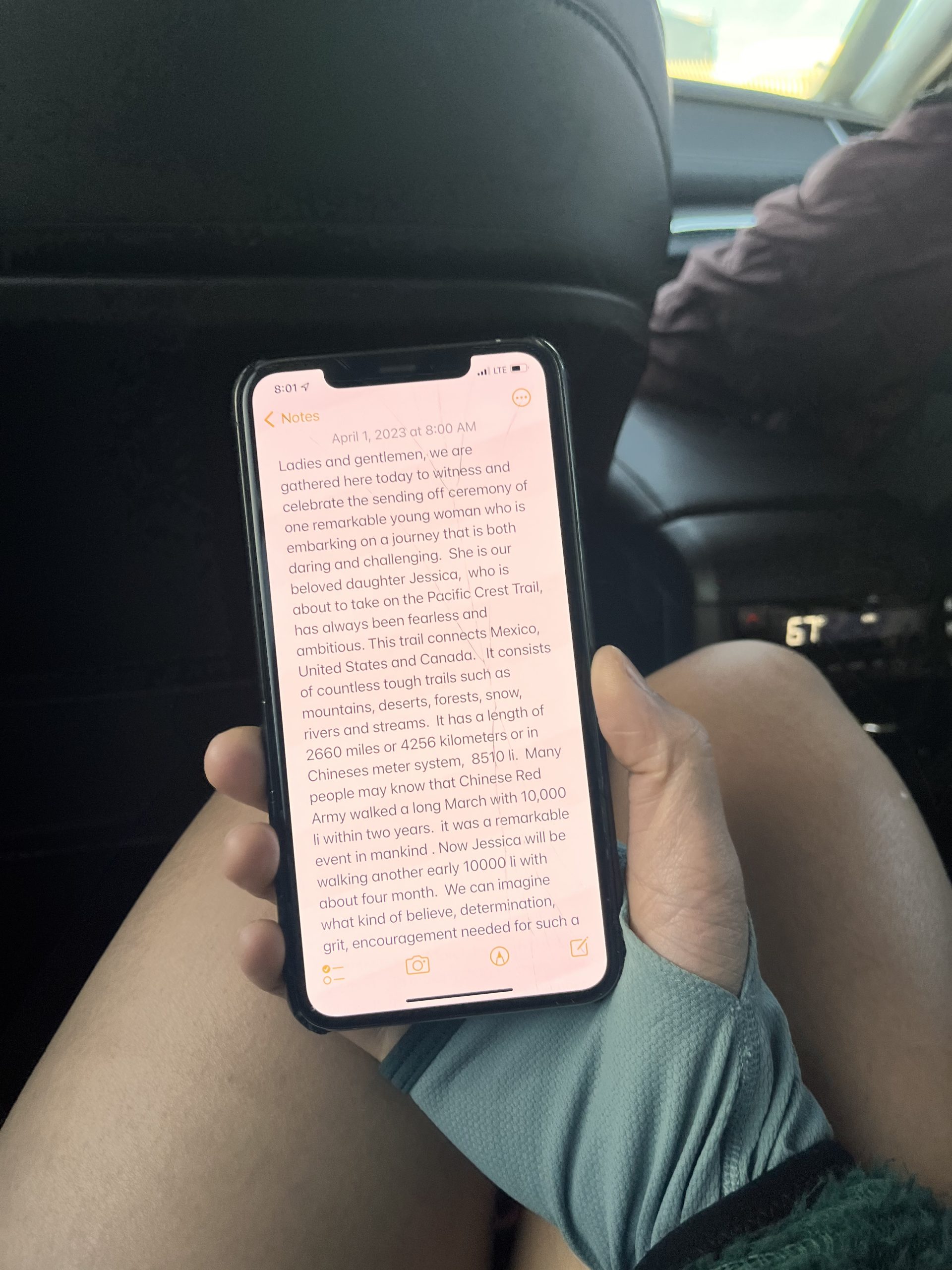

You will cry when you come again upon the text of your father’s send off speech to you on the morning of your departure, which he delivered at the base of the southern terminus monument, to an audience of four of your family members and a pair of volunteers and a handful of other hikers who were all strangers to you at that time.

You will remember his initial response when you said you wanted to hike this trail: why? And then in this speech he reminds you of the answer so that you can take it with you. He wrote it himself in his second language, English—but, endearingly, did not finalize without asking you to edit the speech for grammar. You, the one born and bred as native into this breathtaking, wild country.

The author editing the text of her father’s speech.

But there is beauty in knowing you share this deeply personal experience with others who know the same love and loss

And so, weeks after leaving the trail, when you’re reminiscing by watching Youtube recaps of other people’s hikes and see the same shots of the same laundromat in the same town of Shasta, you will exclaim (as I did in the comments of a fellow hiker & Trek blogger Yeehaw’s absurdly well done film): there! It was there in that corner that I changed behind a tarp held up by my hiking partners so I could wash the clothes on my back. There! that glimpse of the blue metal which only the inculcated will recognize it as the legendary Stehekin shuttle. There I was. There I am.

To borrow a concept from meditation: in everything, we are always looking for ourselves. We are attached to everything that is ours, everything that we claim as an extension of what is in the orbit of ‘mine’. In everything, we are always looking for ourselves. Our face in the group portrait. Our friend in the crowd. The right words with which to craft our bio. The oddly shaped mushroom at mile marker 1209.6, did anyone else see that? The jokes we left on FarOut for each other. The Instagram stories of other hikers we might have met but to whom we might not yet have been introduced. Our footprints at the 1500 mile sign we had to make ourselves. Where we left our mark.

This trail is ours. That is what inspires others to take up the love story. They are not all content to simply read and savor your memories. They want to make their own.

These little collected, collective memories will be what make you weep in their specificity to your experience. Yours, and that of several thousand others, like the way you might feel about a love song that feels like it’s written for you, specifically, then attend a concert where you’re singing ‘your’ song along with a million other people. You still know it’s your song, but you love that you can sing it with everyone else who also thinks it’s their song.

That’s how it feels to finish a thru hike. You have your specific memories of it that make it special to you, but it’s beautiful that there are so many people who have their own memories of this trail that was so transformative for you.

Because that is also part of the appeal of this love: the sacred one-ness of its entire population having experienced, each in their own way, the same single track across a landscape.

You can’t stay on trail forever, but you can go back again, again, again.

The author at the northern terminus of the PCT.

xx

stitches

[ad_2]

Source link